This blog entry explains how an old house might have dealt with rain and dampness when it was first built, what could have happened since to change that and ways of reinstating the original balance.

If the fabric of an old building allows water vapour to enter but dry out again, this is called ‘breathing’ and means that damp can dry out harmlessly.If water is trapped inside the walls of an old house by impervious materials or finishes it can cause decay.

A genuinely old building usually relies upon this ‘breathing’ but when the pores and surfaces that permit this to take place have been sealed up then problems can occur.

1 How old houses cope with rain

This section explains how traditional roofing and external wall materials worked.

The original builders of old houses had little in the way of genuinely waterproof materials which were both cheap and readily available. The challenge was to provide a good roof and walls out of the more accessible materials.Thatch, for roofs and mud for walls are perhaps at the more extreme end of the scale but they illustrate the principles:-

A thick layer of thatch laid at the correct angle will absorb some rain but deflect the majority. If the thatch also overhangs the walls sufficiently then it will help keep them dry. Following rain the air can circulate between the thatch stems and allow it to dry out ready for the next shower.

A wall of compressed earth would easily dissolve if allowed to get too wet, so it is built on a stone or brick base to keep out as much ground dampness as possible. But some damp will still percolate upwards so it is important that the wall is not sealed higher up so it can dry out.

The walls of earth buildings were often coated with a thin skin of earth plaster and covered with limewash, both are breathable materials and help smooth the surface to deflect rain.

After rain, any water that has been absorbed by the walls and roof can dry out. The same principle also applies to some extent to other traditional constructions, clay roof tiles and brick walls for example.

Traditional roof coverings such as tiles, wooden shingles and slates, had to be interlaced, like a fish’s scales, to be able to cover a large area. This allowed for air to circulate between each tile or slate and also allowed for movement.Old buildings are often prone to move slightly, this was allowed for in their construction and decoration.

2 Condensation and old houses

This section looks at the causes of damp from within a building; how it was dealt with traditionally and the consequences of modern occupancy of old houses.

Condensation has been a problem in some twentieth century homes because the amount of washing, bathing, showering and cooking in modern households produces a lot of water vapour in the air.

This vapour turns back into water when it hits a cold surface, such as a window pane. If it finds a cold surface deep inside the construction of a wall then it deposits the water there, this can give rise to hidden decay.

The way to remove steam or water vapour is by keeping rooms well-ventilated and surfaces just warm enough to prevent the vapour condensing into drops of water.

When most old houses were built solid fuel fires would have been commonplace. These needed plenty of fresh air to help the fuel burn; air was drawn from the gaps around doors and windows. This circulation of air helped to draw out any damp in the structure.

Nowadays the balance has changed and central heating has often been installed in old houses, which provides heat but not ventilation. The gaps around doors and windows are usually sealed up and chimneys blocked up to prevent cold draughts. Kitchens, bathrooms and showers are generating water vapour in the heart of the house. Consequently there is a lot of water vapour in the house looking for somewhere cold to go and turn back into liquid. Water lodged in bricks and stones can gradually destroy them by the repeated action of freezing and expanding. Water in the timbers of an old house can mean decay because it makes the wood attractive to fungi and beetles.

3 How old houses dealt with damp in walls and floors

This section looks at the way that ‘rising’ damp was accommodated in old construction; how some twentieth century finishes proved incompatible with this and how remedial measures attempted to solve the problem.

Moisture can enter from the ground around and underneath an old house. Traditional materials were not able to banish damp from entering in the first place (as modern construction aims to do). So some dampness was accepted and this could be dispersed by ventilation.

The building materials and finishes available to builders of old houses were usually ‘breathable’, allowing water to evaporate out of them. Dampness was able to travel through the fabric and decorations until it reached a place where it could dry out, either in the sun and wind on an outside wall or drawn into internal ventilation and out through chimney flues.

Traditional finishes such as clay floor tiles or lime-washed or distempered walls are examples of materials that can allow damp to pass through on its way to dry, without necessarily spoiling the surfaces.

A present day problem is that during the twentieth century new paints and floor and wall finishes were developed that were suitable for modern buildings but these were also used on old houses.

Some characteristics of some of the new finishes, for example being glossy and washable, often also meant that they were less vapour-permeable than traditional finishes. Consequently they might stop the building drying out adequately and ‘bottle-up’ dampness, resulting in blistering and staining.

Instead of acknowledging that perhaps old houses needed to behave differently and be furnished differently to modern houses, there was a demand for applying various damp-proofing systems to old houses to try to make them behave like new ones.

When building a new house it is relatively easy to see that all the damp-proofing measures are in the right place. However it is less easy to see what is going on when the potential pathways for damp are hidden inside an unknown old house construction. Sometimes extra layers of relatively impervious renders were added as an extra barrier. This further decreased the vapour permeability of the structure, making ‘breathing’ more difficult.

A simpler solution can sometimes be possible and effective. That is to return to the way the house was intended to deal with damp. This means allowing maximum acceptable ventilation, together with appropriate heating and using only suitable ‘breathable’ finishes inside and outside over a totally ‘breathable’ fabric.

4 Reinstating traditional principles of damp-management

This section examines how far it might be possible to turn back the clock towards traditional damp management and points to areas of concern:

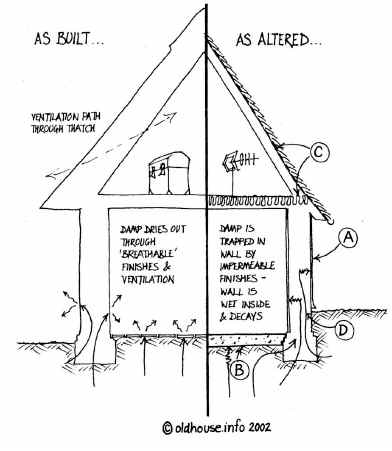

The sketch below shows, on the left, a simplified traditional damp management regime, here on an earth-walled house. On the right is shown what may have happened to that house in recent times to disturb the equilibrium.

The following headings A, B, C & D describe, with reference to the illustration, some general situations that are likely to be found in practice. It is not possible here to examine every possible variation but this will introduce some general problems that may be encountered.

Situation A The ‘breathability’ of the external wall has been reduced.

This can happen when an old wall is rendered in cement or painted with a ‘waterproof’ paint (or even when a brickwork wall is re-pointed in cement mortar).

In many cases the hardness and impermeability of these new applied materials was incompatible with the soft, porous and moving structure beneath. If the new coatings developed tiny cracks, as a result of movement or loss of adhesion, then water could enter and begin the process of decay.

Sometimes it is possible to remove ‘plastic’ masonry paint, it is less easy to remove cement render (unless that has already lost its ‘key’ to the wall) and it is often very difficult to remove cement pointing to brick or stone work without damaging the bricks or stones.

The traditional exterior renders, paints and mortars were often based on lime which, though less ‘waterproof’ than modern alternatives, are usually more ‘breathable’ and better suited to the way old houses can move very slightly. They are available nowadays to use.

Removing existing finishes can be a serious intervention and suitably qualified impartial professional advice may be needed. In the UK Listed Building Consent may be necessary for listed buildings. Planning Permission may be necessary for an unlisted building in a Conservation Area. Building Regulations/Building Standards approval may also be needed if changing certain features of the building. Ask the planning and building control departments at the local government authority.

If it seems appropriate to leave cement render or plastic paint in place then it is quite important to fill cracks – even hairline ones – as soon as possible to prevent water getting trapped inside.

Situation B: Partially trapped ground moisture

Sometimes internal floors have been re-laid in concrete over a polyethylene sheet or asphalt or similar ‘damp-proof barrier’. This can make an effective barrier so far as the floor is concerned but it is really a new, modern floor.

But the ground dampness does not simply go away and can be deflected by the new floor into the internal and external walls and, once there, can ‘overload’ the existing arrangements in place to cope with damp.

Solutions very much depend upon individual circumstances and impartial suitably qualified advice should be sought. Remember that, if you live in a listed building the interior is just as much part of the listed building as the exterior and permission will be needed for any alterations.

Situation C: Sealing up of roof ventilation

The illustration shows original thatch having been replaced with tiles. This was a common change often made long ago. Provided the tiles allowed the passage of air between them, the ventilation was not inhibited.

But at some time, as shown by the illustration, the tiles may have been re-laid using a roofing felt underlay beneath the tiles. By itself, or in combination with roof insulation pressed too hard into the eaves, this change can obliterate much of the natural ventilation in the roof, leading to decay or mould-growth.

Fortunately this can be relatively easy to deal with, there are a number of unobtrusive proprietary or ‘custom-made’ vent designs which can be installed. Also, if re-roofing with underlay, there are now underlays which claim to be ‘breathable’ but as these are relatively new products advice should be sought as to the relative ‘breathability’ of each type.

When considering re-roofing, permissions as mentioned under ‘Situation A’ above may be needed, even if you are exchanging a replacement modern roof finish for a type that is more likely to have been found on the old house originally.

Situation D: Bridging between ground moisture and wall

Where soil or leaves have built up against an external wall to above the floor level, dampness can be transmitted into the wall and into the house. Other variations of this problem are hard-surfaced paths which allow rain to splash up the wall or which trap damp in the soil near the wall.

Broken, leaking or blocked rainwater pipes and gutters can be continually wetting an area of wall. It is easy to miss this unless the gutters and downpipes are observed during heavy rain.

It can usually be a simple matter to level soil, taking care not to expose the foundations of an old house, which can be remarkably shallow.

Cutting back or removing paths can be a harder task but there can be benefits in the reduction of damp if the paths immediately adjoining an old house are made of gravel instead of concrete or asphalt.

This can also be the area in which a remedial damp proof course has been installed in the past and which may, if there are problems, perhaps either not be functioning fully, or it may be acting to block benign migration of damp out of the wall.